Wildlife Articles

The Wall Lizards Podarcis of the Iberian Peninsula Anthophora plumipes Ivy Bee

A guide to Norfolk's Crickets Wasp Spider

All content and images are ©Perry Fairman Ecological Experiences unless otherwise indicated

Wall Lizards Introduction

In May 2018 a trip to Spain see (The Spanish Pyrenees, Belchite Plains & the Ebro Delta) included three main areas: Spanish Pyrenees, Belchite Plains and the Ebro Delta. Several species of Lizards were seen and photographed here, as they had been in previous visits to Spain.

In all cases, I am lucky enough to have someone to identify these Lizards in Mike Linley who is a very well respected Herpetologist and wildlife film-maker.

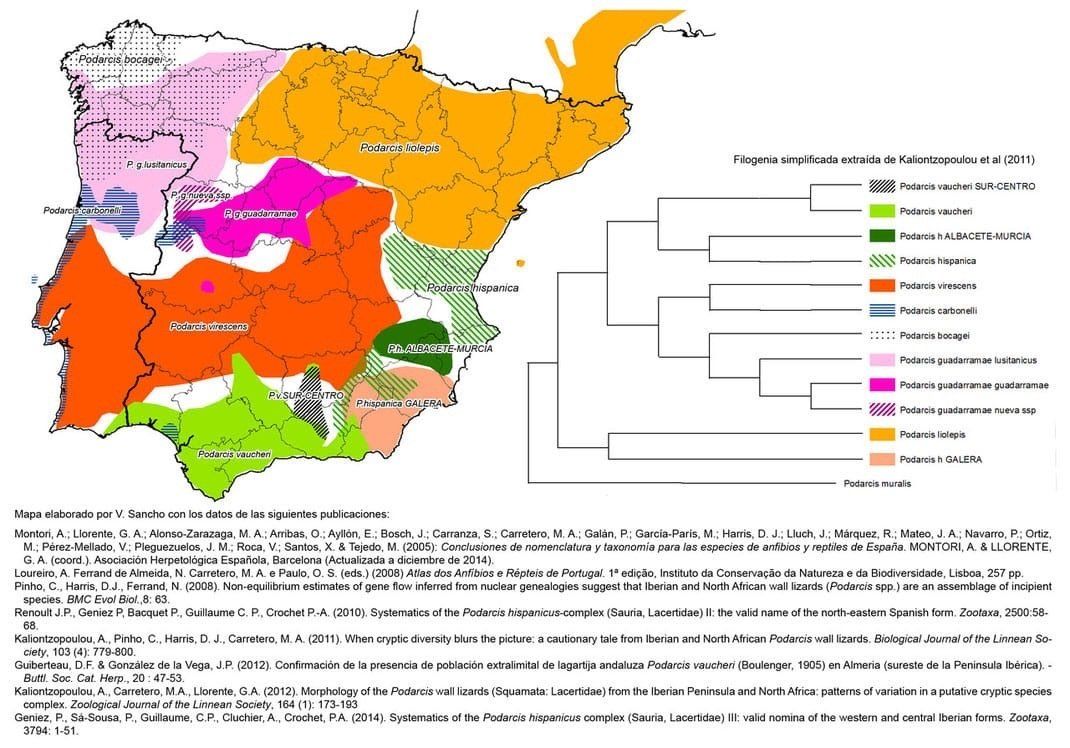

On returning from the trip I consulted Mike and was given privy to a distribution map, that at the time had yet to be published. With his help and from the map's details I was able to identify the Wall Lizards I had seen.

I hope that in publishing this map and introduction from Mike it may help others, in going some way to identifying what they see on the Iberian Peninsular.

The Wall Lizards Podarcis of the Iberian Peninsula

MIke Linley

Many of the reptiles observed by birdwatchers as they travel through Spain and Portugal are both relatively easily observed and readily identifiable. Not so the ubiquitous “Wall Lizard”, often spotted either basking in the sun or scuttling up the favoured habitat of rocks, walls, and buildings.

When I was a schoolboy a single species, Lacerta muralis, was said to be distributed over much of Europe, including the whole of Spain and Portugal. But even then, on my family holidays, it was clear to me that there was a huge variety in their colouration and markings depending on their location. Now, after several years of work, a friend of mine, Vicente Sancho and others, has separated and identified the species that occur throughout the Iberian Peninsula, all now assigned to the Genus Podarcis.

The geography of Iberia, high mountains and sierras, rivers and valleys have led to isolation and speciation over millions of years and several ‘ice ages’. Below is the distribution map of Podarcis in Spain and Portugal which you might find useful on your travels in the future.

If you’d like to read more and see photographs of the species, you can view them here.

https://esoescomotodo.jimdofree.com/reptiles/podarcis-hispanica/

Mike Linley.

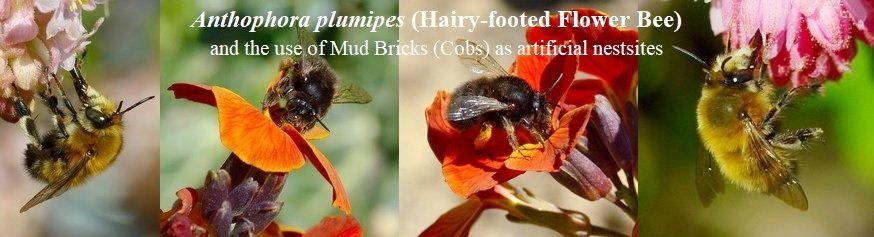

Anthophora plumipes is the name I have always known this Bee as, after identifying it some years ago from Michael Chinery’s book: ‘Collins Guide to the Insects of Britain and Western Europe’. Since those days, the vast majority (if not all!) of Bees have ‘common names’, but I can’t see how the name of Hairy-footed Flower Bee really helps to identify it, or to narrow it down as a ‘flower bee’!

However, this attractive and in my mind charismatic Bee is very sexually dimorphic (males and females appearing completely different) early-emerging species (March-early June).

I will leave the description to Dr. Nick Owens from his book, ‘The Bees of Norfolk (pp 174 and for further information), which says:

Females have black hair except for the hind tibia and tarsus, which have orange pollen collecting hairs and the tongue is very long in both sexes.

Males are largely ginger-brown and are often mistaken for Carder Bumblebees. They have a large area of pale yellow on the long face and a pale yellow marking beneath the antennal scape. They often have long hairs on the mid tibia, giving the species its common name.

I usually see these Bees visiting Flowering Currant flowers or those of Three-cornered Leeks in my garden in Martham, Norfolk but for a more comprehensive look at A. plumipes flower preferences see:

The Foraging Preferences of the Hairy-footed Flower Bee (Anthophora plumipes (Pallas 1772) in a suburban garden, by Maggie Frankum, 3 Chapel Lane, Knighton, Leicester LE2 3WF

This will also give you an idea of what plants to include in your garden, in order to attract these Bees.

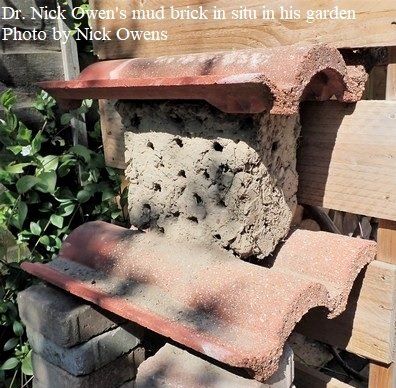

In addition to A. plumipes flower preferences, there is also a way to encourage them to nest in your garden (which I have only recently learnt about), via ‘Mud Bricks’ (Cobs) ‘invented’ by John Walters.

Dr. Nick Owens first told me about these structures and suggests the following:

‘You need just clay soil, dead grass, pebbles/gravel and water. Mix it in a bucket then make a mould for the brick/s out of wood or tiles. It needs to be about 15 cm from front to back. Leave it in the sun to dry then push a bamboo cane in to make holes of about 5 – 10 cm deep while the brick is still soft. The Bees will use the holes and excavate brood cells leading from these.’

I can see different ‘recipes’ evolving over time for these excellent additions to the garden for our declining Bee population, but for John Walter’s ‘recipe’ see his

You Tube video.

As a former teacher, I can see the benefit of these ‘Bee-bricks’ for informing school pupils about Solitary Bees and the creation of them is a very good practical lesson along with continued observation and differing levels of theory for differentiation purposes.

Thanks to Dr. Nick Owens for telling me about the ‘mud brick’ nesting site and his knowledge. Also, to John Walters for his terrific invention and enhancement of gardening for Bees and Maggie Frankum for her article on Foraging Preferences.

A guide to Norfolk's Bush Crickets

Bush Crickets have very long antennae, often exceeding the body length. Females have a ‘blade-shaped’ ovipositor at the end of the abdomen for egg-laying. Adults can be found between July and November, although the nymph stages can be found before this, particularly Dark Bush Crickets.

Oak Bush Cricket Meconema thalassinum

A small delicate Cricket, which is mainly pale green with a yellowish-white stripe on the dorsal side of the body, found in woodlands, hedgerows and gardens. Can be seen during the day but also at night when I have seen them coming through an open window, drawn by the light.

Great Green Bush-cricket Tettigonia viridissima

A large Cricket, which has a pale brown stripe along its back, and the wings exceed the length of the abdomen. Found in grassland, overgrown hedgerows with Brambles and also in reedbeds. Only found in a few places in Norfolk, particularly around the Reedham area.

Dark Bush-cricket Pholidoptera griseoaptera

A bulky dark brown Cricket found in woodland edges and hedgerows (where it tends to favour Brambles) and rough grassland. I have had this cricket turn up in the kitchen sink after being drawn to light on one occasion.

Roesel’s Bush-cricket Metrioptera roeselii

A dark brown dorsal area with a cream margin around the sides of the dark pronotum and three pale spots on the sides of the thorax are what to look for in this species. It is found in rough grassland and indeed lush grassland especially next to water (e.g. Thompson Common’s Pingos) and in roadside vegetation.

Bog Bush-cricket Metrioptera brachyptera

A brown and green cricket with green underside and the rear side of the pronotum has a cream edge. Look for this cricket in damp heathlands (e.g. Holt Lowes). Due to the habitat preference, this species is much localised.

Long-winged Cone-head Conocephalus discolour

A slender green cricket with a brown dorsal stripe. The long brown wings extend beyond the abdomen. Found in both dry and damp grasslands, reedbeds, heathland and woodland edge. Once uncommon in Norfolk but it has extended its range quite considerably. I saw my first one ever when it landed on my arm at Horsey!

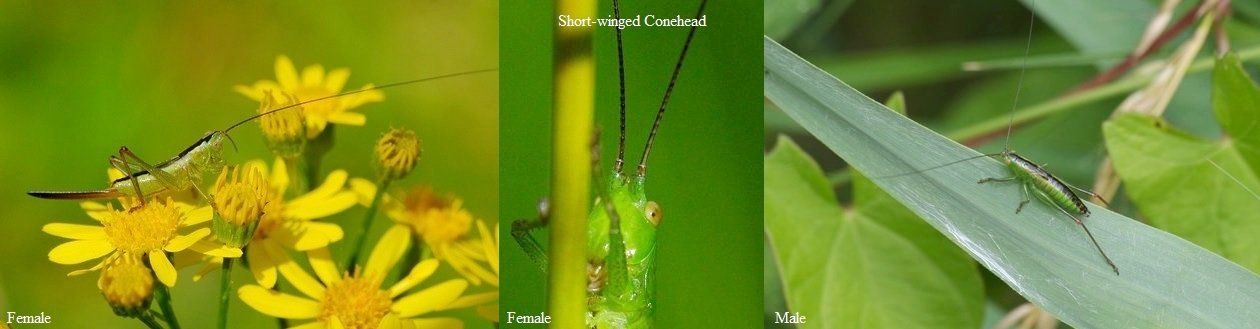

Short-winged Cone-head Conocephalus dorsalis

A small, slender green cricket, with a brown dorsal stripe and wings, which only stretch half way along the abdomen (unlike Long-winged Cone-head). Found in Sand dunes (e.g. Winterton North Dunes along the pool edges), marshes and along the edges and in reedbeds (e.g. Hickling Weaver’s Way).

Speckled Bush Cricket Leptophyes punctatissima

This is a bulky, green cricket with a brown dorsal stripe and dark speckles over the whole body. Woodlands, hedgerows and gardens are favoured and again like some of the aforementioned species Brambles are a good place to look.